Core Stability Through the Breath

A strong and stable core is an essential component of overall strength, function, and healing capacity. An optimal core, however, does not necessarily mean six pack abs! So, what exactly does it mean to have a strong core?

First, let’s begin by defining the “core”

The core is essentially a muscular dome within the abdomen, composed of spinal stabilizers in the back, several layers of abdominal muscles in the front, the pelvic floor muscles on the bottom, and the diaphragm on the top. You can think of these muscles as walls forming a pressurized container; if any of those components don’t perform their tasks well, the container will lose pressure and weaken the stable base you need to move properly.

We can perform exercises to target each component of this intrinsic core system, but it is important to recognize that we are also training these muscles with every inhale and exhale we take. If our breathing patterns are not optimal, we may be enforcing an imbalance in this system that will result in reduced core stability and put us at a higher risk of injury. Breathing is regulated by our autonomic nervous system and therefore occurs automatically, but the pattern of breathing can be changed for various reasons.

What is optimal breathing?

In an optimal breath cycle, the diaphragm will lengthen, depress, and allow the lungs to expand on the inhale.

This creates a horizontal expansion through the lower ribs, combining with the resistance of the pelvic floor and abdominal wall to increase pressure and force air into the lungs. However, when a person sits for hours in a slumped position, the diaphragm cannot perform its job the way it was designed to. There is no room for the diaphragm to expand or depress in this position, so the body must find another option in order to keep breathing.

Secondary breathing muscles will then be recruited to increase chest expansion instead of abdominal expansion on the inhale. This pattern is known as “chest breathing” and utilizes muscles which attach to the upper ribs and neck. The problem with this is these secondary breathing muscles have other jobs related to the upper body, jaw, and head. If these muscles compensate for too long and become overworked, something has to give. The sternocleidomastoid muscles, upper traps, and pectoral muscles will shorten and contribute to a forward head posture and kyphotic spine, which may contribute to dysfunction or pain in the long-term.

It is important to note here that poor posture is not the only contributing factor to altered breathing patterns. While sustained slumping will certainly contribute to this phenomenon, slumping is perfectly natural and good in small doses. Our bodies are meant to move and adapt to our changing positions, as long as we are able to return to our primary natural breathing as our baseline pattern.

The role of the diaphragm

While the diaphragm plays an important role in respiration, it is also essential in providing stability. Maintaining a neutral spine position during activity is believed to protect varying structures from injury.

In a study by Kolar et al., it was found that patients with low back pain had smaller diaphragm excursions and higher diaphragm positioning than those without low back pain. The researchers noted that, optimally, the respiratory function of the diaphragm should be synchronized with the stabilization function. An uncoordinated or insufficient diaphragm activation can lead to overloading of the spinal segments and compromised spinal stability.

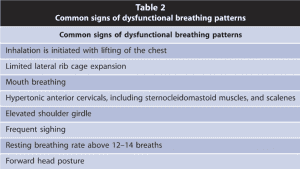

The following table, according to Nelson in the Strength and Conditioning Journal, depicts several indicators of dysfunctional breathing patterns.

So you know how to recognize a dysfunctional breathing pattern now, but how do you retrain your body to breathe optimally again?

The following activities can be used as starting points for retraining the breath. It is important to note, however, that the dysfunction was likely created over years of adaptation, and it may take several weeks-months to change those habits.

It has been proven that short bouts (~10 minutes) of practice performed several times throughout the day are most effective in changing breathing patterns, and that over-attention to the matter may have detrimental effects on the practice as it will not allow the nervous system to adapt properly.

Here are some exercises to implement throughout your day to optimize your breathing and core stability:

- Pursed lip breathing: breathe in through your nose for 2-4 seconds and very slowly exhale through the mouth with pursed lips for 4-8 seconds. Imagine blowing at a candle flame enough to make it flicker but not go out.

- Guide the breath: lay on your back in a quiet area. Plays one hand on your chest and one on your abdomen. Take some relaxed breaths and notice the movement of your hands. Ideally, the hand on the belly should rise before the hand on the chest. The hand on the chest should move forward and not upwards toward the chin. Imagine a balloon inflating inside your abdomen, expanding 360 degrees with each inhale.

- Reduce shoulder movement: Sit in a chair with forearms and elbows comfortably supported by the arms of a chair. As you breathe in through your nose, gently push down onto the arms of the chair. As you exhale through pursed lips, relax the arms.

- Tune in to your transverse abdominis: Lay on your back with your knees bent, with feet slightly apart. Place a yoga block or a similar object between your thighs, and place your fingers on your lower abdomen between your front hip bones (ASIS). On an exhale, engage the pelvic floor and squeeze the block lightly as you let your belly button drop. You should be able to feel the transverse abdominis muscle pop up under your fingers. On your inhale, relax and soften the belly.

Final Thoughts

Once normalized breathing patterns have been achieved, spinal stability exercise can be introduced while the breathing rate is elevated. One method shown by McGill is to ride a bike with enough intensity to elevate the breath, and then immediately dismount the bike and assume a side plank posture. The purpose of this exercise is to combine the functions of postural control and respiration and encourage resilient motor patterns.

As evident in current research, functional breathing and core stability are complex phenomena that go hand in hand. While the above practices are good starting points to understand your own breathing habits, it is best to utilize the help of a professional to optimize your breathing patterns. With the correct assessment and interventions, you can retrain your core and reverse or protect your body from injury.

About the author:

Emily Lowry is a student physical therapist graduating from Texas State University in May 2022. Ms. Lowry completed a clinical internship in physical therapy at the Anchor Wellness Center under the study of Drs. Sarah Crawford and Samantha Dove, PT, DPT, located in Cincinnati, Ohio. Ms. Lowry has a special interest in yoga therapy and outpatient orthopedics.

References:

Kolar P, Sulc J, Kyncl M, Sanda J, Cakrt O, Andel R, Kumangai K, Kobesova A. Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 42: 352–362, 2012.

McGill S. Low back stability: From formal description to issues for performance and rehabilitation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 29: 26–31, 2001.

Nelson, Nicole MS, LMT Diaphragmatic Breathing, Strength and Conditioning Journal: October 2012 – Volume 34 – Issue 5 – p 34-40 doi: 10.1519/SSC.0b013e31826ddc07